(Disclosure: I am not an NDP member, nor am I supporting any candidate in the leadership race.)

One of the responsibilities we have, if we want to live in a real democracy, is to avoid being fooled by quasi-democracy: political systems that provide an illusion of choice and participation, but in reality exclude people and are driven by elite interests.

For example, in the Liberal leadership race earlier this year, the outcome didn’t match the will of party members, confirming that other forces were in play.

Now the NDP leadership race has begun, and I’d like to dispel any illusions that this will be a democratic vote either. Yes, it’s true that all members will have the right to participate in the final vote. But the ballots will be tainted before members lay hands on them, because of contest rules that favour wealthy campaigns and disenfranchise certain members.

In this post and my next one, I’ll explain two important anti-democratic elements of the NDP leadership race: the entry fee system, and centralized control over vetting, sanctions, and rule changes.

The entry fee system: inequality at work

To enter the race, each candidate must fundraise an entry fee of $100,000. The fee is payable in four instalments, with the first $25,000 due when the candidate applies.

The problem is, supporters of different candidates have different levels of disposable income. Take a look at these fundraising statistics from the 2017 NDP leadership race:

| Candidate | Dollars raised | Donors | $ per donor | Donors to reach $100,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANGUS, Charlie | $476,065.07 | 4936 | $96.45 | 1037 |

| ASHTON, Niki | $297,433.13 | 3941 | $75.47 | 1325 |

| CARON, Guy | $246,304.08 | 1863 | $132.20 | 756 |

| SINGH, Jagmeet | $924,902.64 | 6484 | $142.64 | 701 |

| total | $1,944,704.92 | 17,224 | $112.90 | 886 |

In the 2017 leadership race, the average donation to Jagmeet Singh had double the dollar value of the average donation to Niki Ashton. (Many supporters of Ashton belonged to groups with less disposable income, such as students.)

If these candidate were running in the 2026 race, Singh would need only 701 donors to raise the $100,000 entry fee, while Ashton would need 1,325 donors. And even if both of them eventually succeeded, Singh would be confirmed as a candidate much sooner, giving his campaign an advantage.

We don’t yet know the roster of candidates for the 2026 race, but the same differences in disposable income will exist, creating the same unfairness. This is no better than those examples in history of laws that explicitly give certain people only a fraction of a vote. In practical terms, the message to candidates is: ignore young members, ignore members of marginalized groups, and focus on those wealthy donors if you want to get in the door!

It gets worse though: candidates are also allowed to pay the first $25,000 of the fee from their personal funds. In other words, a wealthy candidate could literally buy their way into the contest—without raising a single dollar from NDP members. By contrast, a grassroots candidate would need to fundraise the full $25,000, and they’d need to accomplish that with no guarantee that their application will even be approved. (More on that problem in my second post.)

The worst part of all this is that the NDP could easily have chosen a lower entry fee and banned self-donations. No complicated rules or systems are needed, just better decisions.

The red herring of “fundraising ability”

Party officials have publicly defended the entry fee system as a way of testing a candidate’s fundraising ability, but this explanation doesn’t hold water.

There are many skills a party leader ought to have: fundraising, yes, but also public speaking, leading a team, conducting themselves honourably, and so forth. The contest rules don’t count how many speeches a candidate has given, or how many teams they’ve led. Members are expected to judge these qualities themselves, so why the special requirements around fundraising?

Besides, entry fees don’t really test fundraising ability. When you see that a candidate has raised $25,000, you don’t know whether that came from a self-donation, from a network of wealthy friends, or from doing actual work: holding town halls, building a mailing list, connecting with communities of members, and so on.

Even if the $25,000 does come from real work, a party leader’s direct personal outreach could never fund an entire federal election campaign. The real “fundraising ability” that a party leader needs is the ability to inspire the public, and that can’t be measured by paying an entry fee.

The whole idea of fundraising ability is a fake talking point; the logic doesn’t hold.

The red herring of “frivolous candidates”

Entry fees are also defended as a way to prevent “frivolous” candidates from running. (Because, as tech billionaires have proven, wealthy people are so much more “serious” than the rest of us, right?)

This argument has already been rebutted by the Canadian courts.

Prior to 2017, candidates paid a fee of $1000 to run in a federal election. That fee was struck down in a 2017 court ruling, because it infringes on our Charter right to participate in elections. Importantly, the purpose of the $1000 fee was specifically to “deter frivolous candidates”. The judgment described this purpose as “irrational”, because it wrongly “equates seriousness with financial means”.

Three elections later, the proof is in the pudding: with a $0 entry fee, Canadian elections still average only 5–6 candidates per riding, with no epidemic of “frivolous” candidates.

This is another fake talking point and doesn’t justify entry fees.

What’s really going on?

If entry fees don’t test fundraising ability, and don’t deter frivolous candidates, what do they actually accomplish?

One thing entry fees are good for is facilitating a particular three-way transaction:

- A candidate with the right connections brings wealthy donors to the party. In exchange, they get to become party leader.

- The wealthy donors make big donations. In exchange, they get to influence party policy.

- Party insiders and consultants make sure the leadership rules favour candidates with the right connections. In exchange, they get contracts paid from those big donations.

Great, everybody benefits! Except party members and the public, of course.

If you find that explanation too conspiratorial, try this one: entry fees are a form of austerity. Party elites, who made bad campaign decisions that created financial debt for the party, use entry fees to divert member donations to repay those debts. Just like government austerity, this “balances the books”, but harms everyone in the long term (as we’ll see further below).

Interim payments: a hidden penalty on grassroots candidates

I mentioned above that the entry fee is payable in four instalments, with the first instalment of $25,000 due when applying.

The second instalment of $25,000 is due on October 31st, and any candidate that hasn’t paid the first two instalments on time is barred from participating in the first debate in November.

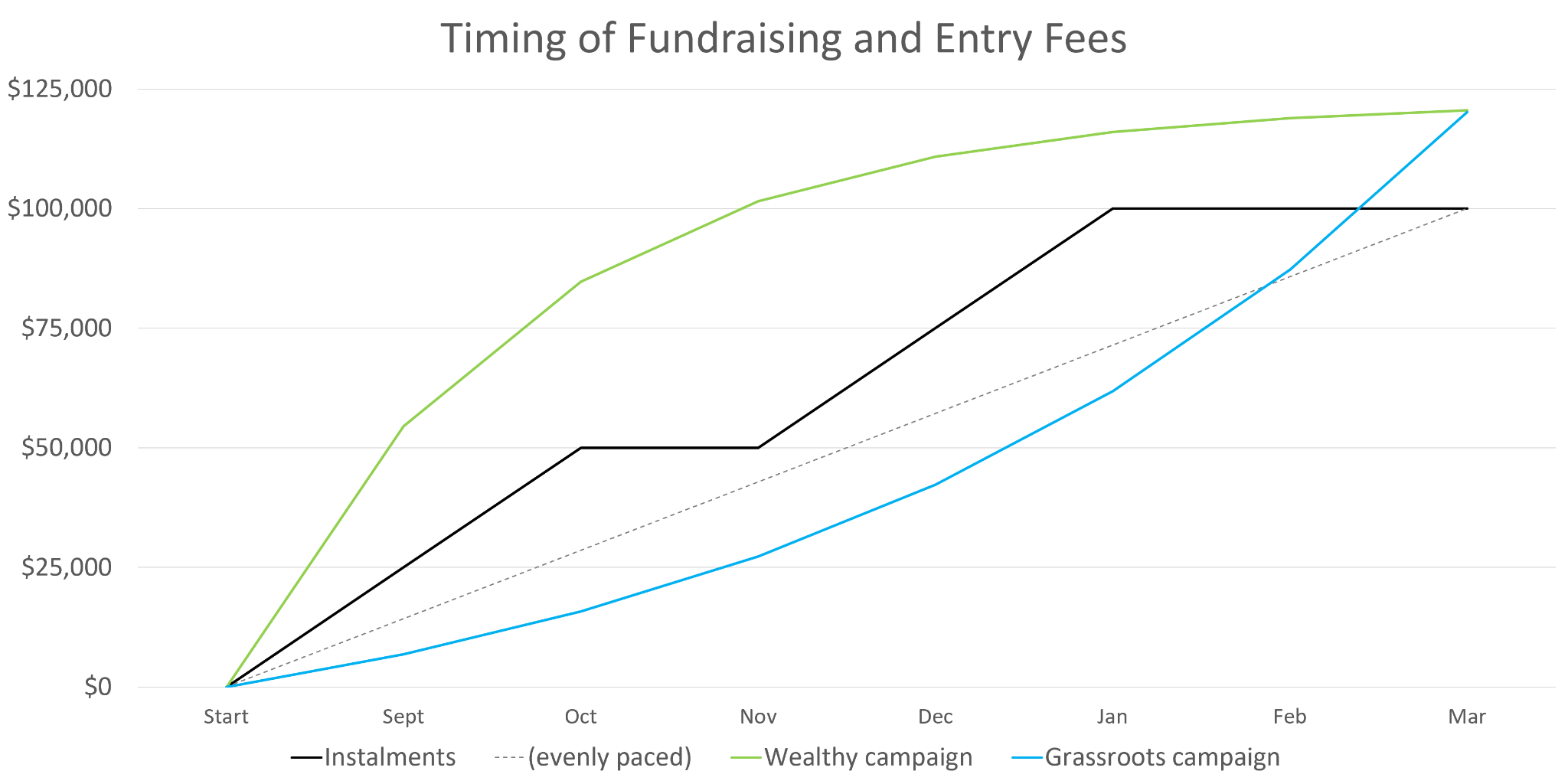

The problem here is that candidates have different patterns to their fundraising. Wealthy campaigns often start with a big self-donation, plus other day-one donations from a network of wealthy contacts—then they tend to slow down. Grassroots campaigns tend to start slowly, but as their message spreads, their fundraising accelerates throughout the contest.

In the graph above, we can see how this might play out in the 2026 NDP leadership race. A wealthy campaign would have no trouble paying the instalments, while the grassroots campaign would struggle, despite both campaigns raising $120,000 by the end of the race. (The graph also shows how much the instalment schedule has been accelerated, compared to an evenly paced schedule.)

Party elites typically dismiss this problem by claiming that “everyone pays the same fees”. But the amount of the fee isn’t the point, the timing is.

As long as there are interim payments that penalize late payers, grassroots campaigns will be disadvantaged compared to self-funding wealthy campaigns.

Artificial scarcity: limiting candidates and campaigns

Donations are not unlimited. The public might contribute more or less to a particular leadership contest, depending on their level of interest, but the amount is still finite. Let’s call this the “money pile”.

The money pile funds all spending by all candidates, including payment of entry fees. The higher the entry fee is, the more of the total money pile it absorbs, creating artficial scarcity and leaving less money for any other purpose. This is the “entry fee austerity” I mentioned earlier, and it damages the party in a number of ways:

- Smaller candidate roster. The money pile can only pay a certain number of entry fees; this caps the number of candidates that can enter the race. However, the cap is much lower than you might think, because entry fees and real campaign expenses compete for a share of the money pile. Calculating based on past leadership races, the $100,000 entry fee will likely cap the NDP leadership race to four or five confirmed candidates.

- Less diverse roster. The candidates that end up being excluded are more likely to come from marginalized groups, or represent minority viewpoints, so the roster ends up less diverse.

- Less party-building. Scarcity increases the pressure on candidates to focus their time on fundraising, rather than “unprofitable” activities like learning from members, building unity, developing useful ideas to improve the party, and so on. Transactions replace interactions, and members feel like piggy banks rather than participants.

- Timid campaigns. Scarcity increases the pressure on candidates to avoid principled stands that might risk offending potential donors, instead focussing on vague statements about “values”.

- Pandering to wealth. Scarcity also increases the pressure to pander to wealthy donors, who can provide more money in fewer donations compared to widely-spread grassroots members.

- Less total fundraising. Ironically, higher entry fees can reduce total fundraising, even though they increase the pressure to raise funds. Successful campaigns often experience a “snowball effect”, where the campaign begins to grow exponentially and bring in more members from outside the party. But when most of the early money is needed for entry fees, less early outreach is possible, and the snowball effect is delayed. Just like compound interest, starting later means you lose the most productive weeks that would’ve happened at the end of the campaign.

- Hidden advantage for higher-dollar campaigns. Suppose one candidate raises $300,000 and another raises $200,000. Once they each pay the entry fee, their real campaign budgets will be $200,000 and $100,000. The first candidate originally earned a 3:2 advantage in campaign spending, but now has a 2:1 advantage instead because of the entry fee.

The larger the entry fee becomes relative to the size of the money pile, the worse these problems get.

Now consider that in 2024, the NDP received 6.6% fewer donations than it did in 2016. Meanwhile, the entry fee for the current leadership race is 233% higher than the entry fee was in 2017.

Conclusion

The effects of high entry fees are much worse than just personal unfairness to candidates. They corrupt the leadership race by giving a strong advantage to wealthier campaigns, by treating members unequally, by suppressing the voices of marginalized people, by encouraging timid and pandering campaigns, and by reducing the non-financial and long-term benefits of the race.

A leadership race with high entry fees can never be democratic. The NDP will continue to defend their decision by claiming that the entry fee system is necessary to test fundraising abilities, or to prevent frivolous candidates, but these are both irrational arguments.

Ultimately, they’ll fall back on the mantra that “members have the final word”. But in a real democracy, members would have the first word, the middle word, and the last word, because the process would belong to them from start to finish.

This is the essence of quasi-democracy. When somebody promises you the “final word”, they’re admitting that somebody else had a say before you. The ballot that NDP members mark in the spring will be a curated ballot, adjusted to suit the priorities of the wealthy and sideline minority perspectives. ●

In my follow-up to this post, I’ll look at how the NDP leadership race includes centralized control over vetting, sanctions, and rule changes, and how this encourages self-censorship, self-exclusion, and internal conflict.

Leave a comment