Canada’s most recent election had a result we haven’t seen in almost a century: the top two parties both got more than 40% of the popular vote. Smaller parties fared very poorly, with the NDP and Greens losing half their support from the previous election, and the Bloc Québécois losing a third of their seats.

Does this mean we’re moving toward a two-party system?

Certainly, it seems to be something that political scientists, journalists, and strategists believe is possible. However, a recent poll by Leger Marketing showed only 21% of Canadians think a two-party system would be a good thing, while 49% think it would be bad.

If you care about politics in Canada, this isn’t just a theoretical question. When you give your vote, time, or effort to a political movement, you hope to see results. To make judgments on where your contribution will be effective, you need to know if the political environment in this country is about to change.

So is the talk of a two-party system just an over-reaction to a single election? Or is this where our politics are headed?

Wait, Aren’t We Already There?

First, let’s get something out of the way. Isn’t there a pretty good argument to be made that Canada’s Parliament has always been a two-party system?

After all, every single government from 1867 to 2025 has been formed by either the Liberal Party, the Conservative Party (under various names), or on one occasion in 1917, a Union government bringing together members of the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party.

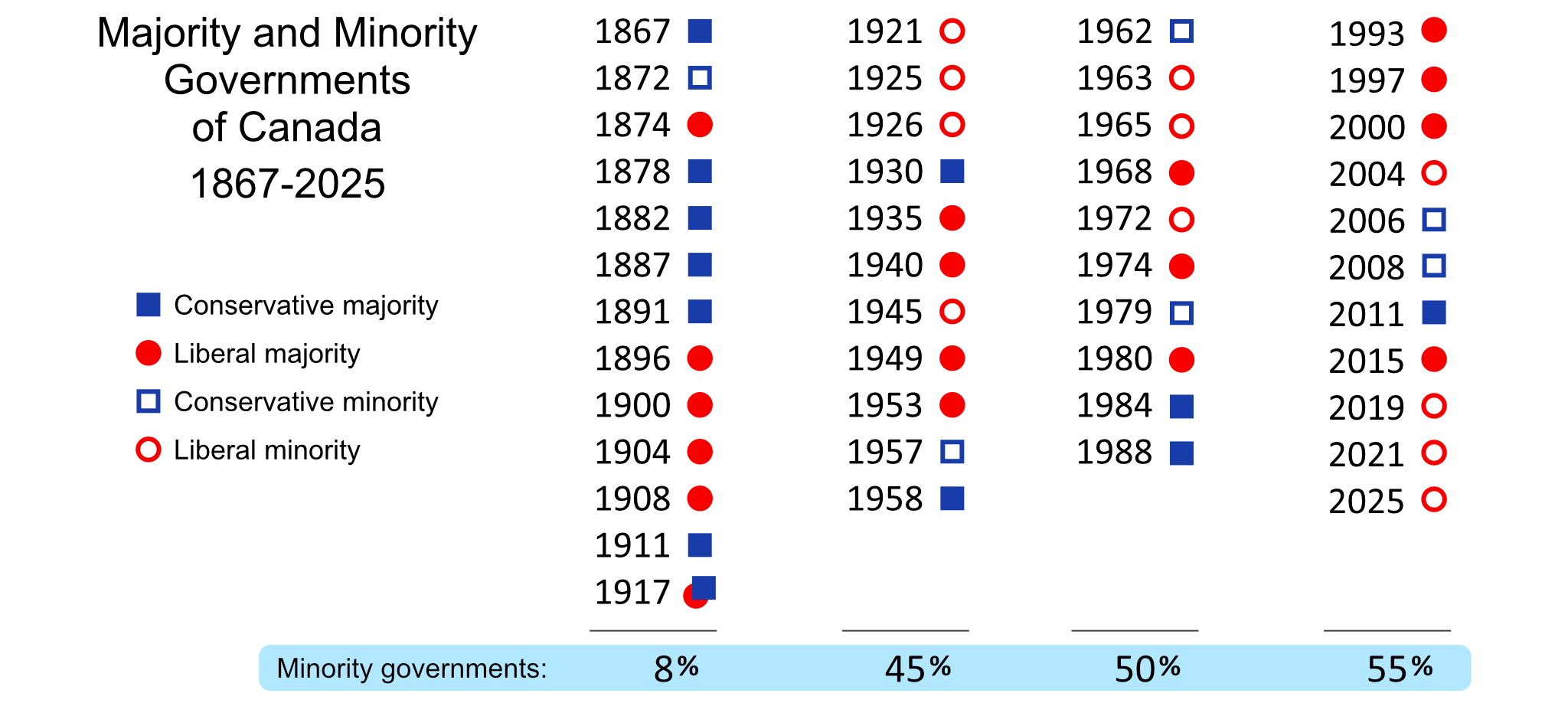

Not only that, but in all but two of those elections, the official opposition was either the Liberals or Conservatives as well. Take a look:

The two times that a party other than the Liberals or Conservatives formed the official opposition were the Bloc Québécois in 1993 and the NDP in 2011. Both times this happened, the Liberal-Conservative dominance was immediately re-established in the next election.

If the same two parties take turns being the government and opposition more than 95% of the time, isn’t that the very definition of a two-party system?

Well, not so fast. We’re leaving something out here.

Don’t Overlook Minority Governments

Out of Canada’s 45 general elections, 17 have produced minority governments. A minority government needs the support of a third party to pass bills and survive confidence votes. Sometimes, a minority government will try to figure out this support one vote at a time, but this creates a lot of uncertainty, and the governments that do this usually don’t last more than a year. More often, a minority government will establish a working relationship with a third party, making some policy promises in exchange for consistent support.

So, even though the third party isn’t formally a part of the government, its ideas and priorities are being incorporated into the government’s agenda. And if that’s happening frequently, then what we have isn’t purely a two-party system.

In Canada, there have been two distinct eras of minority governments:

Prior to the 1962 election, minority governments usually relied on the support of independent MP’s who were, in reality, associated with the governing party. For example, the Conservative minority government of 1872 had the support of several “Independent Conservatives”, and the Liberal minority of 1945 was supported by “Independent Liberals”.

The only exceptions to this rule before 1962 were the Liberal minority governments of 1921, 1925, and 1926, which were supported by the Progressive party. However, even these MP’s were actually former Liberals, who had recently split off from the party due to the issue of conscription in the 1917 election! (Many of them would end up returning to the Liberal Party.)

In other words, before 1962, there really was a two-party system: Liberals and Conservatives always formed government, they were supported by Liberals or Conservatives if there was a minority, and their opposition would also be Liberals or Conservatives.

However…

From the 1962 election onward, minority governments were usually supported by third parties. For example, the 1962 Conservative minority government relied on the support of the Social Credit Party, and the Liberal minority governments of 1972, 2004, and 2021 all relied on support from the NDP. Other times, minority governments in this period relied on support from a mix of third parties.

Minority governments have been getting more common since confederation:

In fact, since 1962, minority governments have been more common than majorities. That means that half of the governments in this period have incorporated the ideas and priorities of third parties.

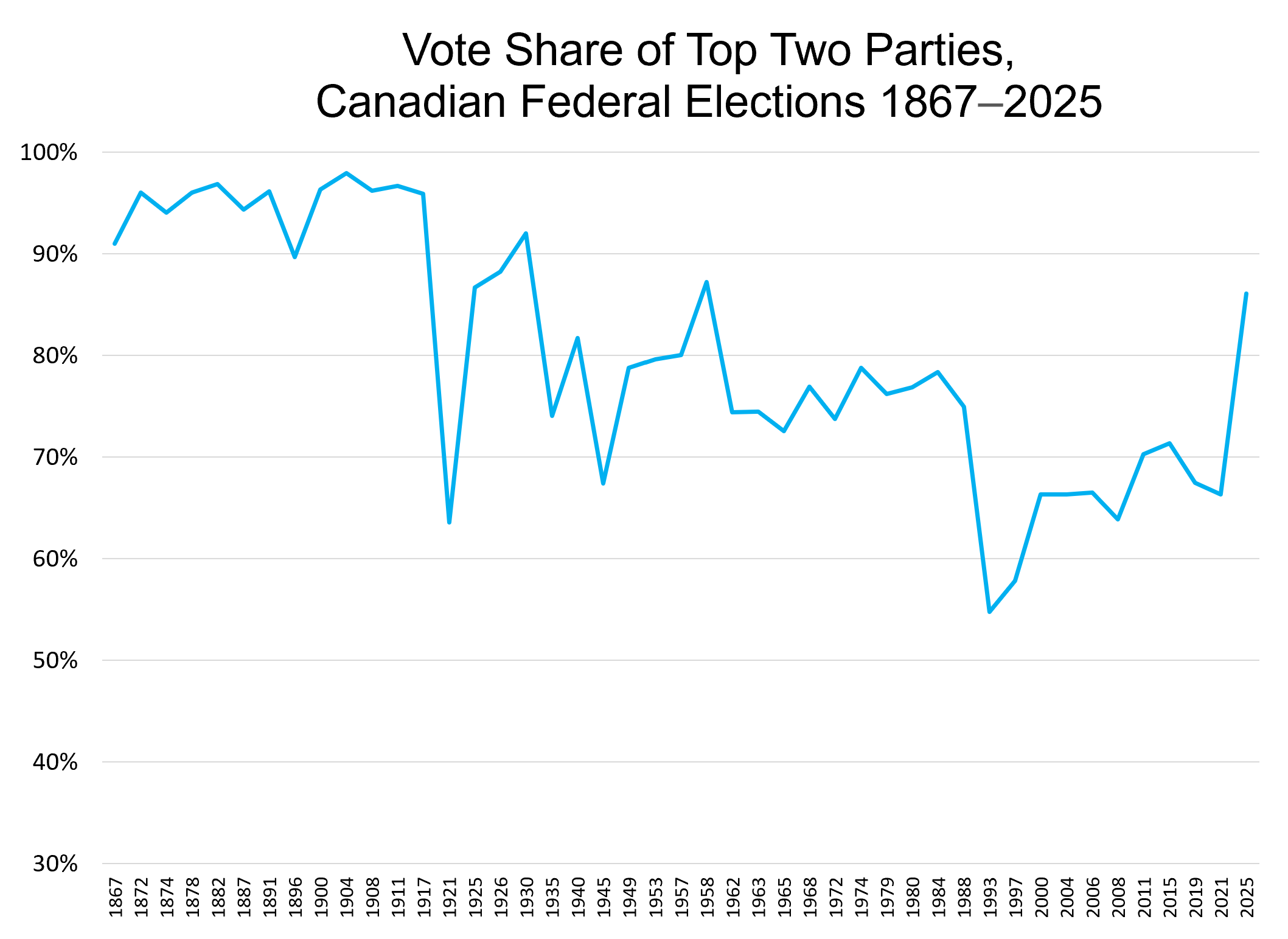

Another way to think about this is to look at how much of the popular vote goes to the top two parties combined. This number has been steadily decreasing since the 1920’s:

When you consider these facts about minority governments, I think it’s fair to say that we’ve been moving further away from two-party rule since confederation. Minority governments are happening more often, and while they started out getting support from like-minded independents, they nowadays depend on the support of third parties.

However, even this doesn’t tell the whole story.

A Growing Number of Parties

When it comes to parties beyond the “big two”, Canada has gone through several distinct eras.

Before 1921, third parties had little impact. In 1867, the Anti-Confederation party won all but one seat in Nova Scotia, and in 1896, the Patrons of Industry (a pro-farmer party) and McCarthyites (an anti-Catholic and anti-French-Canadian party) were each elected to two seats. In every other election before 1921, the Liberals and Conservatives were completely dominant, combining for at least 94% of the popular vote.

From 1921–1930, the aftereffects of the First World War resulted in a temporary multi-party system. The Progressive Party (discussed above), working with the United Farmers, captured a combined 21.9% of the vote in 1921. A new Labour party also contested these elections, and was elected to a handful of seats. Support for the two major parties totalled only 63.6% support in 1921. However, these additional parties quickly disappeared: most Progressives returned to the Liberals, and Labour and United Farmers faded over the next few elections. By 1930, support for the two major parties had rebounded to 92.0%.

In the 1935 election, things changed drastically. In the midst of the Great Depression, with trust in both the Liberals and Conservatives at a low level, a total of seven parties were elected to seats in the 1935 Parliament. Although several of these new parties would fade away, two endured for decades: the Social Credit Party (a western conservative party and loose predecessor of Reform) and the Co-Operative Commonwealth Federation (a socialist party and predecessor of the NDP). This four-party configuration lasted until 1979, and during this time, the share of the top two parties averaged a much-lower 77%.

By the 1980’s, Social Credit had collapsed, and there was a brief three-party system consisting of the Liberals, Progressive Conservatives, and NDP. Despite the smaller number of parties, the share of the top two parties remained in the mid-70% range.

The 1993 election brought a new five-party system, with the creation of the Bloc Québécois and breakthrough of the Reform party, which captured 13.5% and 18.7% of the popular vote respectively. The share of the popular vote taken by the top two parties dropped to its lowest level ever at 54.8%. In the 1997 and 2000 elections, the conservative vote remained split between the PC and Reform parties, maintaining the five-party configuration.

In 2004, the PC and Reform parties merged to form the modern Conservative party, creating a four-party system that lasted for three elections. The top-two party share of the popular vote was in the mid-60% range in this period.

As of 2011, a five-party configuration was restored when the Green Party entered Parliament, although it has struggled to expand beyond a few seats. The top-two party share of the popular vote has been just under 70% in this period, except in 2025, when it spiked to 86%.

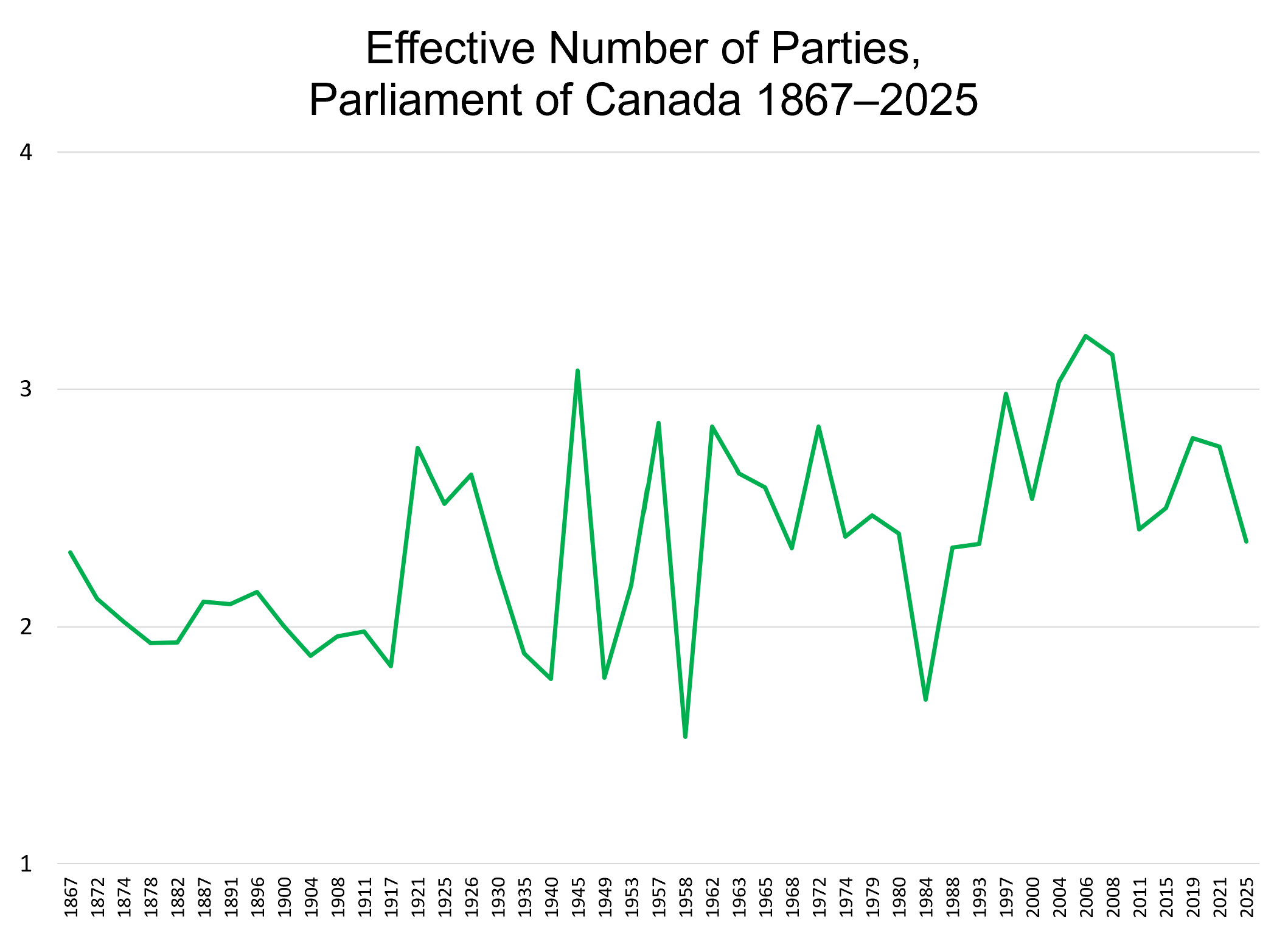

We can visualize all of this using a measurement called the effective number of parties. The ENP counts the number of parties in Parliament, but also takes into account whether one of those parties is dominant, or whether they are strongly competitive with one another.

For example, a three-party Parliament where the seats are evenly divided among the parties would have an ENP just below 3. But in a three-party Parliament where one party is dominant and has three-quarters of the seats, the ENP would be much lower, around 1.7. In other words, the ENP helps to distinguish between genuine multi-party systems, versus systems where extra parties exist but have no impact.

The ENP tends to jump up and down between elections, so it’s best to look at it over the long term. Since 1867, Canada’s ENP has risen from an average of 2.0 to an average of 2.6:

When we look at all of these variables together—the declining share of the top two parties, the increasing number of minority governments, and the increasing number and importance of smaller parties—we can see that over the long term, Canada has been moving away from a two-party system, not toward it.

Will the Trend Continue?

Still, no matter what the long-term trend has been, we’ve just had an election that went strongly in another direction. The top two parties captured a combined 86% of the popular vote, a result more reminiscent of the 1800’s, and the Effective Number of Parties was down to only 2.36, a thirty-year low.

Is this a temporary reversal, or a new reality that’s here to stay?

If we look back at previous realignments in the party system, there are some patterns that can help us make an educated guess.

National Threat Effect

In times where the public perceives a national threat from outside, governments have been elected with greater levels of support. This effect disappears again once the threat has passed.

The table below shows the popular vote for the winning party in the elections before, during, and after three different threatening events: the First World War, the Second World War, and President Trump’s 2025 threats of economic warfare and annexation. Each time, the level of support is 5-10% higher than what was typical for that era:

| Threat | Before | During | After |

|---|---|---|---|

| First World War | 48.9% | 56.9% | 41.2% |

| Second World War | 44.7% | 51.3% | 39.8% |

| Trump | 32.6% | 44.3% | – |

It makes sense that in a time of national anxiety due to an outside threat, people would vote more cautiously, would place more value on the idea of a united Parliament and strong government, and would prefer stability to change. Once the threat is over and the anxiety has dissipated, it would be reasonable to expect these effects to disappear.

Post-Threat Effect

However, we can also see that after both World Wars, new parties entered Parliament, and the vote share of the top two parties dropped substantially:

| Top Two | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior Threat | Election | New Parties | Previous | Now |

| First World War | 1921 | Progressive, United Farmer, Labour | 96% | 64% |

| Second World War | 1945 | Bloc Populaire, Labor-Progressive | 82% | 67% |

These new parties might arise because of grievances over how the outside threat was handled, such as the controversy over conscription during the First World War. Or, they might represent groups who felt they were ignored or pushed aside during the threat. Or, the new parties may represent new ideas the public wants to explore now that the threat is gone.

Systemic Crisis Effect

Times of economic or systemic crisis also bring new parties into Parliament, while also shaking up existing parties:

| Systemic Crisis | Election | New Parties | Punished Party | Previous | New |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Great Depression | 1935 | Social Credit, CCF | Conservatives | 137 seats | 39 seats |

| 1990’s Recession | 1993 | Bloc Québécois, Reform | Progressive Conservatives | 169 seats | 2 seats |

| 2008–09 Financial Crisis; Climate Change | 2011 | Greens | Liberals | 77 seats | 34 seats |

Unlike times of national threat, where the threat is outside the country and there’s a desire for unity and strength, a systemic crisis is a time when people lose trust in existing parties, institutions, and ideologies. This could lead to the public punishing an established party for failing to deal with the crisis or for seeming out of touch with the times. It could also lead to the public supporting new parties that are presenting alternate approaches.

What to Expect After 2025

I’ve pointed out these three effects because I believe the 2025 election was a unique combination of an outside threat and a systemic crisis at the same time.

Prior to Trump winning the election in November 2024, the top political issues in Canada were economic concerns: housing affordability, rising cost of living, precarious work, and income inequality. Other important issues from previous elections, such as climate change, had been pushed down the list of priorities for voters, and fears of war were extremely low on the list. During this time, the Liberals were experiencing historically low polling numbers.

However, after Trump was elected, his threats of trade war and annexation triggered a wave of anxiety, causing a massive migration of voters to the Liberals—in particular, older voters who were more economically secure and saw Trump as the top priority.

This shift to the Liberals looks like a clear case of the National Threat Effect, but it came at a time when we might have been building toward a Systemic Crisis Effect. So what happens next?

Let’s assume that by the time of the next election, the threat of Trump has subsided, but dissatisfaction with our economic situation has continued to grow. We might expect to see a combination of the Post-Threat Effect and the Systemic Crisis Effect that had been delayed. If so, we should expect a drop in the vote share of the top two parties, along with increased distrust in existing parties and institutions and increased interest in new ideas, creating an opening for new parties to enter Parliament.

For example, a hypothetical 2027 election result might look like this:

| Party | Vote % |

|---|---|

| Conservatives | 33% |

| Liberals | 28% |

| NDP | 16% |

| Bloc Québécois | 10% |

| New Party | 7% |

| Greens | 3% |

| Others (no seats) | 3% |

In this scenario, the effective number of parties would reach a new high of 4.1. The vote share of the top two parties would be a fairly low 61%, and we would almost certainly have a minority government.

Of course, other outcomes are possible. For example, the Conservative party, which hasn’t been in power since the 2015 election, might be given a chance to solve the economic crisis, possibly delaying the Systemic Crisis Effect until the 2031 election. Or, the current Liberal government might manage the crisis effectively enough to alleviate that pressure (though, as I discussed in Carney’s Honeymoon of Contradictions, that will be hard to). Or, an existing smaller party might successfully reinvent itself and reap the benefits of the Systemic Crisis Effect.

Looking at the big picture, I think there’s good evidence that the 2025 election was a unique event that pushed us closer to a two-party system, but only temporarily. I expect that over the long term, Canada will continue to move in the opposite direction.

Leave a comment