It’s been a tough few years for the Green Party of Canada, and the 2025 election was no exception: after being kicked out of the leader’s debates, the Greens fell to 1.2% popular support and lost MP Mike Morrice by a heart-breaking 375 votes, leaving them once again with Elizabeth May as their only MP.

Regardless of how you might feel about the Greens (and there are plenty of critiques to go around), their consistent presence in the leader’s debates and media coverage ensured there were always science-based targets anchoring the climate policy discussion in Canada.

However, that time is over. As bad as the last two elections may have looked on the surface, the numbers behind the scenes are much worse. The Green Party is effectively dead.

Now, when I say the Greens are “dead”, I don’t mean they’ve been formally deregistered. That may not happen for several years.

What I mean is that their ability to influence the public conversation is permanently lost. They aren’t going to be included in future leader’s debates, they aren’t going to elect more than one or two MP’s in future elections, they will largely disappear from media coverage, and any attempts at a comeback will fail.

Whether you were ever a Green supporter or not, this is an important change in the political landscape in Canada. Other parties will adjust their positions, catering more openly to business interests and cynical vote-chasing, while fact-based targets will increasingly need to be supplied by media, activists, and experts.

However, as negative as this sounds, the end of the Greens is a necessary development. In this post, I’ll provide evidence to justify my claim that the Green Party is dead, then I’ll explain why this isn’t such a bad thing for the climate movement in Canada.

The situation today

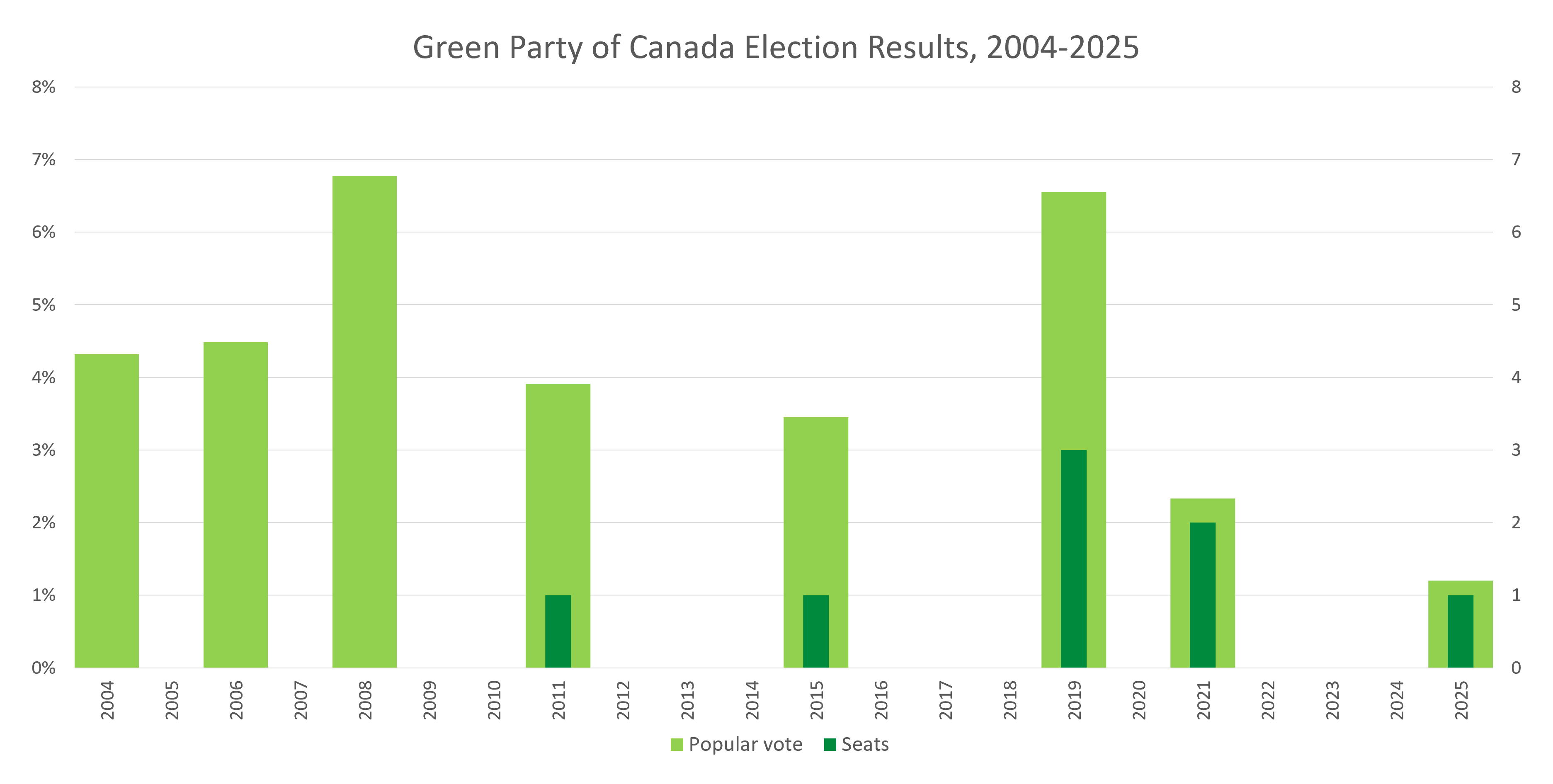

Let’s begin by looking at the Green Party’s election results over time (data sources and methods are detailed at the end of the post):

Before anybody blames the 2025 election result on Trump, notice that it isn’t an outlier—the party’s popular vote has been on a downward trend since 2011.

Since election day, opinion polling for the Greens remains below 4%. This is important as far as future leader’s debates are concerned. To qualify for the debates, a party needs to meet two out of three thresholds: have a seat in Parliament, have at least 4% support in the polls, or run candidates in 90% of ridings.

The Greens still have a seat, but they’re now polling below 4%, and in the last two elections they’ve fallen well short of nominating a full slate of candidates:

During the 2021 election, blame was laid on a “slow” and “bureaucratic” nomination process under Annamie Paul. But with 2025’s nominations being even worse, the problem clearly extends beyond any single leader.

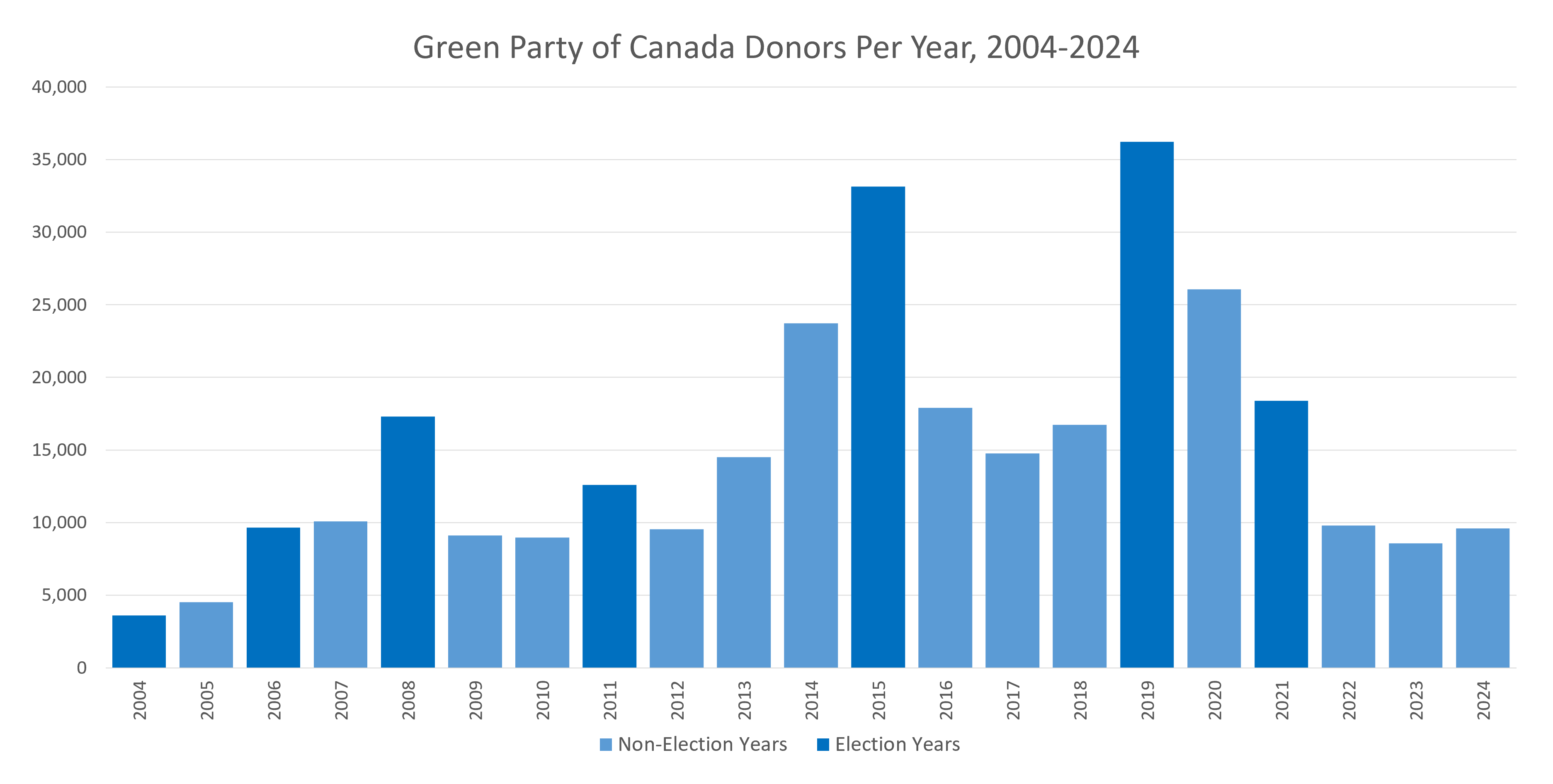

To go along with the declining election results and candidate nominations, the Green Party has also lost more than half of its donors:

The party’s finances became critically tight in 2021, when it was forced to lay off half of its staff and close its head office to avoid running out of money. But in 2022, donor numbers dropped even further, and haven’t improved since.

On each of these four critical measures—seats, popular vote, candidates, and donors—the party is in very poor shape. That’s enough to prove it’s in a crisis, but not enough to prove it’s permanently dead.

Comebacks, plausible and otherwise

Other parties have had crises and recovered. For example, in 2011 the Bloc Québécois collapsed from 49 seats to only four. They went through a string of new leaders, a major drop in fundraising, lost two thirds of their popular support, and lost many of their riding assocations—but in 2019, they rebounded to 32 seats and regained most of their popular vote.

Couldn’t the Green Party have a similar recovery? If they were in the same position as the Bloc, perhaps. But their position is actually much worse.

Here are the top ten results for Green candidates in the 2025 election:

| Candidate | Prov. | Riding | Place | Vote % | Margin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAY, Elizabeth | BC | Saanich–Gulf Islands | 1st | 39.1 | +7.3 |

| MORRICE, Mike | ON | Kitchener Centre | 2nd | 33.6 | -0.6 |

| MANLY, Paul | BC | Nanaimo–Ladysmith | 4th | 18.1 | -17.4 |

| ZAJDLIK, Anne-Marie | ON | Guelph | 3rd | 10.2 | -44.5 |

| PEDNEAULT, Jonathan | QC | Outremont | 5th | 9.6 | -45.6 |

| KEENAN, Anna | PE | Malpeque | 3rd | 3.9 | -53.7 |

| GREENLAW, Lauren | BC | West Vancouver–S.C.–S.S.C. | 3rd | 3.4 | -56.3 |

| ALLEN-LEBLANC, Pam | NB | Fredericton–Oromocto | 3rd | 3.1 | -58.2 |

| DOHERTY, Michael | BC | Victoria | 4th | 3.1 | -51.2 |

| PERCEVAL-MAXWELL, Dylan | QC | Laurier–Sainte-Marie | 5th | 2.8 | -49.3 |

This is pretty disastrous. Across the entire country, the Greens had one win, one near miss, and beyond that… nothing.

Even in their third-strongest riding, Nanaimo–Ladysmith, they lost by a margin of 17.4% and came in fourth. In every other riding in Canada, the Greens finished at least 44 percentage points behind the winning candidate. It’s a far cry from a party that once managed five second-place finishes and a sprinkling of middle-tier ridings to build on.

Individual campaign spending has been getting weaker over time as well. Green candidates who spent at least $10,000 on their campaign could be found in 20% of ridings in 2019, but only 10% of ridings in 2021. (Early financial returns for 2025 suggest this trend has continued.)

Compared to all of this, when the BQ collapsed in 2011 they still had 23% popular support within Québec, along with four seats and more than 41 second-place finishes to build on.

Electing 32 seats out of 45 strong ridings is a plausible feat. Electing three seats in two strong ridings is mathematically impossible.

Worse still, it’s not even clear that the two “strong” Green Party ridings are all that strong in the first place. Take a look at Elizabeth May’s victory margins since her first election win in 2011:

May’s win in 2015 was a triumph, but in the ten years since, her margins of victory have steadily decreased. It’s likely her next election will be a very close race.

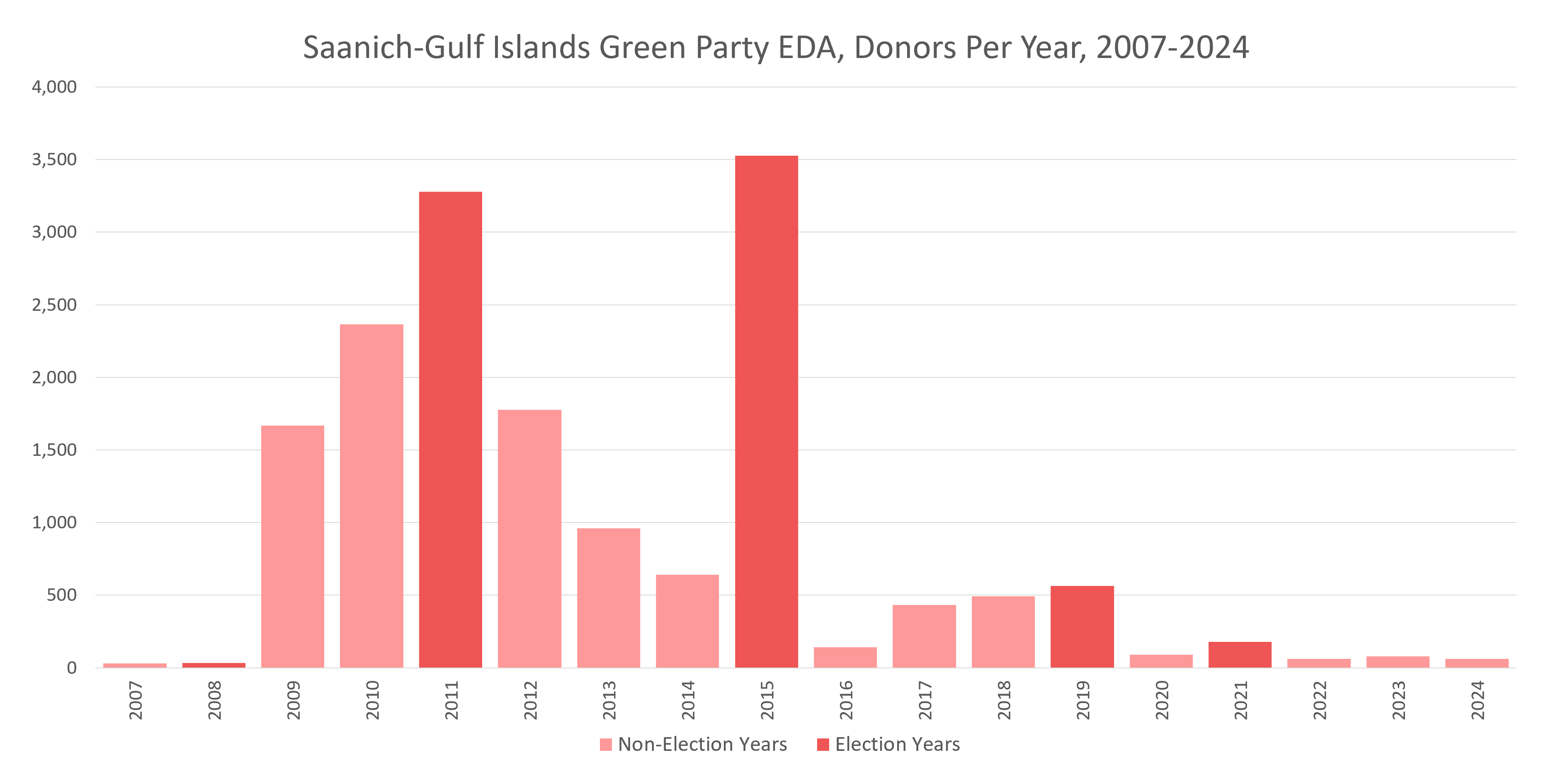

In addition, fundraising in May’s riding of Saanich–Gulf Islands appears to have dried up almost completely since that 2015 win:

Mike Morrice’s riding of Kitchener Centre is similarly not guaranteed. On the one hand, Morrice lost by less than 1% and had strong and consistent local fundraising. But at the same time, his lead over the third-place candidate was only 4%. In the next election, Morrice will have to look both ahead and behind to fend off two strong competitors and regain his seat.

So between May and Morrice, we have two precarious ridings, and beyond that, no other competitive candidates. That’s not enough for a comeback, not even to the very modest three seats the Greens once held. They would need something more to reverse their fortunes.

New recruits?

Let’s assume the Greens manage—somehow?—to recruit a handful of new, high-profile candidates to run in the next election along with May and Morrice.

Those high-profile candidates would need local fundraising support if they hoped to win their ridings.

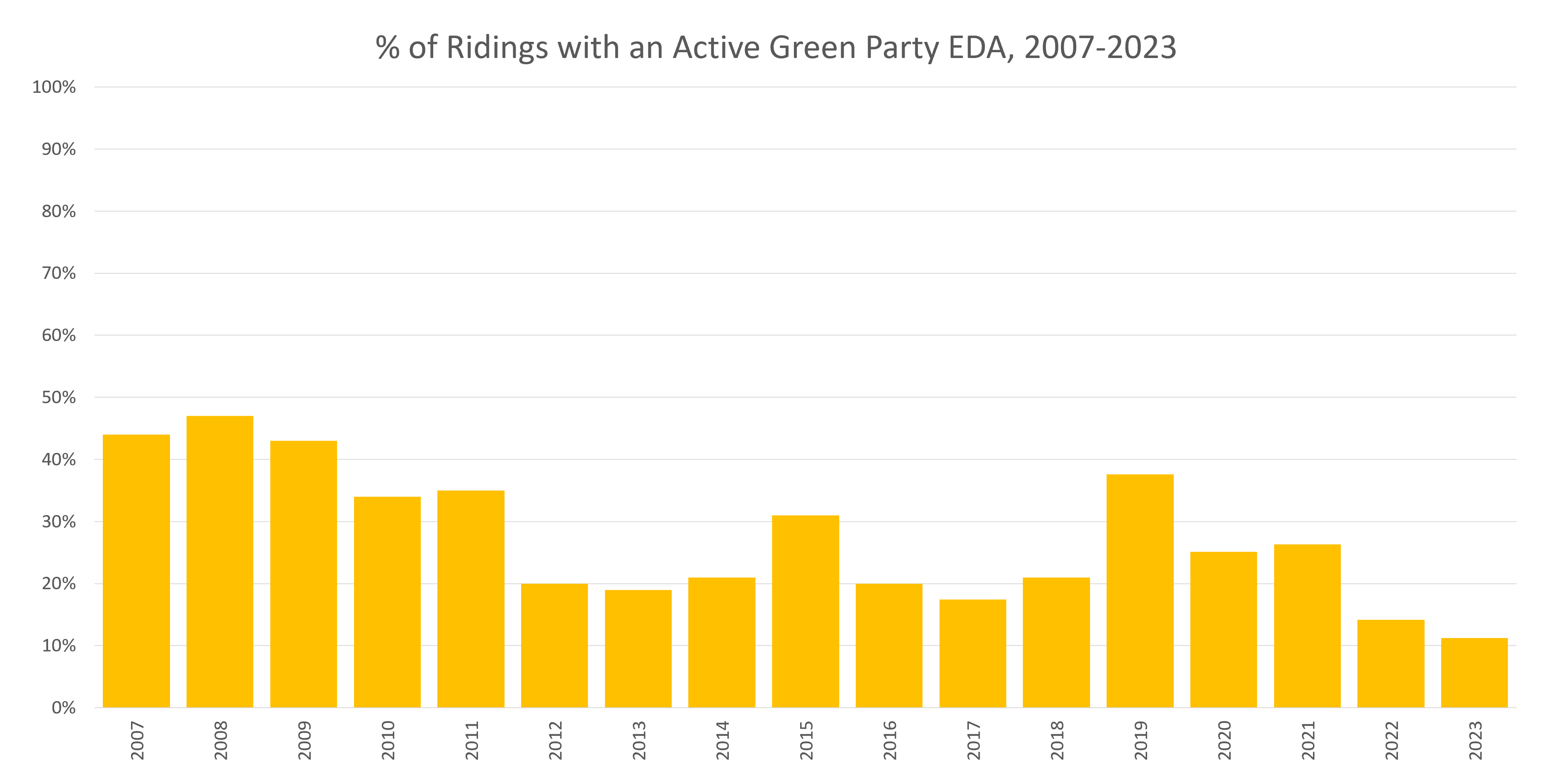

Let’s take a look at how many ridings have a Green Party district association (EDA) that’s financially active:

These numbers have never been great, but are now extremely bad. In 89% of Canada’s ridings, the Greens have no active EDA they could build a campaign on.

What about the 11% of ridings where the EDA is active? As the saying goes, the devil’s in the details, and once you zoom in the picture is pretty ugly.

Here are the top ten Green EDAs as of 2023 (the most recent year with complete financial returns), ranked by number of donors:

| Riding | Donors | Dollars donated |

|---|---|---|

| Kitchener Centre | 144 | $51,536 |

| Saanich–Gulf Islands | 79 | $24,016 |

| North Island–Powell River | 60 | $13,172 |

| Ottawa Centre | 59 | $785 |

| Burnaby North–Seymour | 56 | $165 |

| Burlington | 9 | $1,975 |

| Kingston and the Islands | 7 | $1,451 |

| Dufferin–Caledon | 6 | $1,940 |

| Brantford–Brant | 4 | $3,500 |

| Stormont–Dundas–South Glengarry | 3 | $600 |

We’ve already discussed Kitchener Centre and Saanich–Gulf Islands, where we assume Morrice and May would campaign. Beyond that, it’s shocking how quickly the numbers drop off. By the time we get to just tenth place out of 343 ridings, the EDA attracted only three donations, totalling $600.

Outside of Kitchener Centre, Green EDAs simply aren’t equipped to support a serious campaign.

New leadership?

Let’s try one last scenario. What if the Greens went all-out to recruit a superstar leader to be Elizabeth May’s successor? Couldn’t a new leader potentially refresh the party’s image, bring in new donors and funds, revitalize EDAs, and help to recruit strong candidates?

Depending on a saviour isn’t a healthy mindset for any organization, but let’s set that aside and focus on the question of whether this is even a plausible strategy.

The party has already tried to find May’s successor twice, in 2020 and 2022, and these were the results:

| 2020 | 2022 | change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of candidates | 10 | 6 | -40% |

| Dollars raised | $704,108.30 | $146,849.00 | -79% |

| Donations | 6400 | 721 | -89% |

| Members recruited | >10,000 | 416 | -96% |

| Votes cast | 23,877 | 8030 | -66% |

| Voting turnout | 68.8% | 36.5% | -32.3pp |

| Winner | Annamie Paul | Elizabeth May |

Volumes could be written about the 2020 leadership race, but to make a long story short, the party had a chance at renewal and blew it. Well before Annamie Paul’s election meltdown, many of the ten thousand members recruited in 2020 had begun leaving the party.

The numbers from the 2022 contest reveal how badly the opportunity was squandered: none of the ten candidates from 2020 returned, no big names from outside the party entered the race, donations were down by 90%, the party recruited fewer than five hundred new members (!), and even the party’s existing members didn’t seem to care much, with only one third of them bothering to vote.

If your party’s leadership is no longer of any interest to anyone, any plan that revolves around a new superstar leader is a fantasy.

Summing up

Being a Green supporter requires a certain capacity for either hope or self-delusion, and perhaps as a result, Greens have always been susceptible to wildly unrealistic promises and comeback narratives. As just one example, take Elizabeth May’s six-month plan from the 2022 leadership race: she promises to elect 12 MPs, rejuvenate fundraising, create internal harmony, and attract floor-crossers from other parties.

None of these things came anywhere close to happening in the years that followed. Instead, we have the situation described above.

The Green Party’s seats, popular vote, candidate slates, and number of donors have all continued to seriously decline. As of today, they aren’t in a position to qualify for future leader’s debates.

The party’s only strong candidates in 2025, May and Morrice, will both face an uphill battle in the next election. And they’ll do it without help, as every other 2025 candidate was miles away from winning.

Even if the Greens recruited new, high-profile candidates, there are no strong EDAs that could support their campaigns. Meanwhile, the central party’s ability to fund local campaigns has been drastically reduced because of lost donors.

And even if the Greens held a leadership race, a “hail mary” play to elect a superstar new leader, there’s plenty of evidence that neither the public nor any high-calibre candidates would be interested.

In short, there is no plausible comeback scenario—the Green Party of Canada is dead.

When movements outgrow parties

There’s a paradox in the relationship between electoral parties and movements. On the one hand, it’s movements that create parties and supply them with vitality, direction, and labour. But at the same time, a party can come to represent a movement in the eyes of the public, to the point that the party shapes the public’s response to that movement. In this way, what was once a vehicle can become a millstone.

This is why the end of the Green Party is not a negative event. Many genuinely good, compassionate, and talented people have worked incredibly hard to build and maintain the party; some are still working to keep it alive today. But despite their efforts, the damage the party does to the climate movement has come to outweigh the value it creates.

If a party can’t deliver seats or legislation, but regularly delivers controversy, distraction, and failure, it’s time for that party to step aside.

To insist on continuing to exist, wastefully absorbing the labour and attention of activists and the public, is to selfishly put nostalgia and wishful thinking ahead of actual progress.

The climate movement in Canada has plenty of vitality. Young activists who understand the links between capitalism, climate change, racism, and imperialism are already building a new push for social change. They’re informed, motivated, and developing new tactics and structures suited to the moment.

The Green Party of Canada will soon be gone, but the movement will be fine.

Sources and Methods: All seat counts, popular vote results, donor counts, riding results, and margins of victory or defeat are public information available on Elections.ca or Wikipedia. Where values are given as a % of ridings, this is to compensate for the increasing number of ridings from 2004–2025. Number of candidates: Determined by a count of financial returns. For 2025, by count of the Elections.ca final list of candidates. Donor counts: Taken from annual returns. For 2024, estimated by dividing total donors on Q1–Q4 quarterly returns by 2; this is likely an overestimate. The claim that the party has lost “half of its donors” is true if you compare peak-to-trough for election years or non-election years. If you compare absolute peak-to-trough, the loss is two thirds of donors. Riding associations (EDAs): Number of EDAs determined by a count of financial returns. An EDA was considered “active” if it received one or more donations during the year. Counts of EDAs were divided by the number of ridings to give a percentage. Individual riding data also came from financial returns. Both donors and dollar amounts were included in the table of top EDAs because a healthy EDA requires both. Individual campaign spending: From financial returns, based on campaigns with $10,000+ of direct expenses. Leadership races: Dollars raised and number of donations were calculated by adding donations on candidate financial returns plus “directed donations” from the central party’s financial return. The number of new members in 2020 was verified by comparing vote reports from the party’s online voting system (SimplyVoting) for votes before and after the leadership race, showing an increase in eligible voters (i.e. members). The number of new members in 2022 was too small to reliably calculate in this way. Instead, a list of all donations to leadership contestants was compiled, then compared to all donations to the central party in the preceding two years. Newly-appearing names were treated as new members. (This can potentially overestimate new members, but not underestimate.)

Disclosures: I was a Green Party of Canada member from 2003 to 2022, ran as a candidate in Brampton Centre in 2015, and was a campaign manager on the leadership campaign for Dimitri Lascaris in 2020.

Leave a comment